Ducos de la Haille’s fresco

Legende

Fresque centrale du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée de Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2018

The fresco decorating the edges of the Forum, located in the heart of the Palais de la Porte Dorée and classified as a historic monument since 1987, was the work of Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille (1889-1972), winner of the Prix de Rome for painting in 1922 and a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts until 1949, who was among the painters who took part in the revival of the fresco technique in the early 20th century.

The orders given to the architect of the Palais, Albert Laprade, were to portray the “contribution made by France to Overseas” on the walls of the function room, a place where galas and official events were held during the 1931 Colonial Exposition, with a décor stretching over more than 600 m², created by the painter, his seven assistants, whose names can be read to the left of the entrance, along with his students. We know that the architect of the Palais, Albert Laprade, chose Ducos de la Haille for the Palais décor design partly because the painter had stayed in Algeria during his military service, from 1912 to 1914.

As can be seen in the archives, Laprade had many discussions with the painter on the iconographic programme (the blindfold over the eyes of Justice, the skyscraper over the legs of America, the excessive number of sailing ships…) and the relations between the two men suffered as a result, although Ducos did take into account certain remarks by the architect, particularly regarding the central painting.

Le Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2018

Constituting the back of the scene, opposite the entrance from the Hall of Honour, the large central panel (10 m long by 8 m high), created in 40 days, represents France, an allegory draped in imperial red and peaceful white. She is surrounded by a winged Cupid, a climbing vine, symbol of abundance and wealth, an oak tree symbolising strength, a bay tree symbolising glory and white sails symbolising overseas colonisation.

France extends the dove of peace to the five continents, whose images surround her: Europe offers her hand to her; in the top left, Africa, and top right, Asia, are turned towards her; finally, reclining on the backs of horses rising out of the sea, Oceania and America represent the old and new worlds.

The allegorical figures

This central composition leads into eight paintings representing the “values brought by France to its colonies”, through allegorical figures (beneath the aloof traits of a woman dressed in Ancient style), a speech bubble placed above each one indicating the concept in question in gold lettering and accompanied by illustrations of the different colonised peoples.

Art is represented by a woman arising out of a shell, like a Venus coming out of the waves, and illustrated by archaeological digs, constructions and scaffolding, symbolising architecture. Anecdotally, the portrayal of an architect in a yellow jacket looking at a plan can be recognised as Albert Laprade, a tribute from the fresco artist to the man who commissioned his work.

Legende

Allégorie de l'art - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille.

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

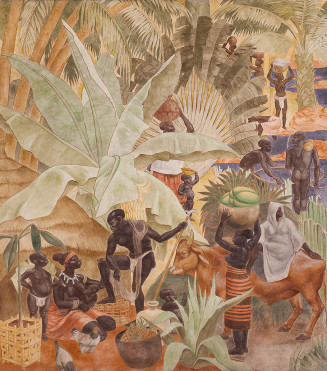

Peace is holding a sickle and a wheat stalk, with a winged Cupid on her shoulder, while at her feet, in the folds of her coat, are a trusting child and a pair of tame deer, with an olive tree on the right. The illustrations to her left show African populations enjoying the prosperity and calm brought by peace, going about their occupations peacefully, while a mother nurses her child, amidst lush vegetation, with chickens and an ox.

Legende

Illustrative composition of peace - Fresco in the Forum of the Palais de la Porte Dorée

Credit

Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée

Allégorie de la paix - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Work is leaning on an ox, symbol of rural work, and on a hammer, emblem of industrial work. The hive, the wheat and the vine complete the picture, illustrated on the right by a peasant working with his plough pulled by an ox, and by woodcutters cutting trees, using both traditional (with elephants) and modern (with tractor in the back) methods.

Legende

Illustrative composition of work - Fresco in the Forum of the Palais de la Porte Dorée

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée

Allégorie du travail - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Trade is depicted by a woman weighing coins on some scales and illustrated by the buzz of activity of a port where, against a background of junks and ships, many different commodities are being exchanged.

Legende

Composition illustrative du commerce - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Allégorie du commerce - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

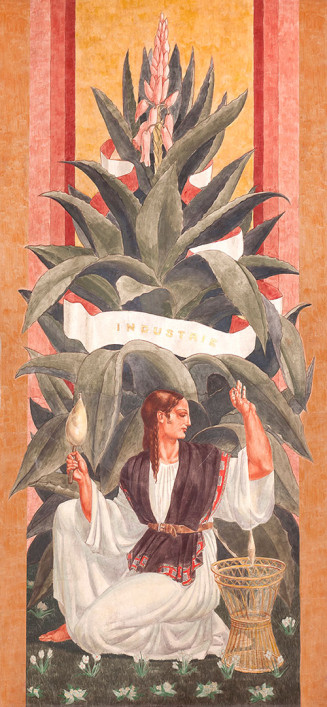

Industry, represented as a distaff spinner, is accompanied by scenes depicting textile workers, and olive pickers busily producing the oil, placed in jars and transported in feluccas.

Legende

Composition illustrative de l'industrie - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Allégorie de l'industrie - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

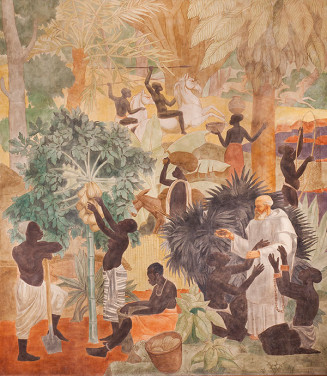

Freedom, in a white dress, her head and red coat blowing in the wind, raising her hand which holds the red Phrygian cap, incites Pegasus, the winged horse, to surge forward full of energy and strength. This theme is illustrated by a white missionary freeing black slaves from their chains and populations enjoying individual freedoms.

Legende

Composition illustrative de la liberté - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Allégorie de la liberté - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Justice is wielding the sword that makes her feared, while strangling the snake, the image of Evil, her eyes blindfolded to express her impartiality, in accordance with Ancient tradition. Behind her, the oak tree and the bison evoke her strength and power. Note that in two letters dated November 10 1930 and April 2 1931, Albert Laprade expressly asked Ducos de la Haille, to absolutely no avail, to remove the blindfold from the eyes of Justice, the reason being that he found it a little shocking to “ridicule colonial justice by presenting it as blind. The fact is that this confusion with the whims of Fortune could be wrongly interpreted and since we are in a public building, we should avoid leaving ourselves open to obvious jokes.” The illustration of the concept of justice makes reference to judgements on disputes between neighbours and assistance given to the weak (the sick, or abandoned children).

Legende

Composition illustrative de la justice coloniale - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Allégorie de la justice - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

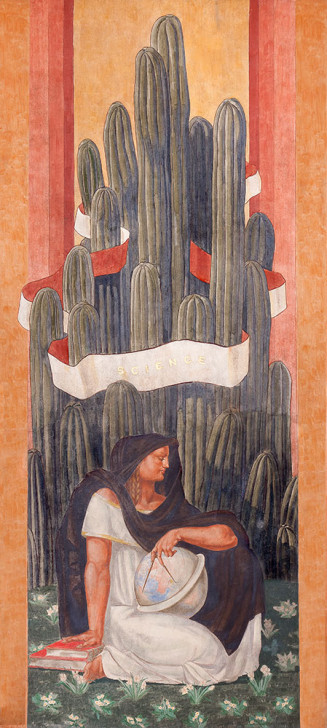

Science, symbolised by the globe and the compass, shows Westerners using modern tools: a nun providing medical treatment, a doctor vaccinating, a surveyor using a sextant, a man making a phone call, with a locomotive in the background.

Legende

Composition illustrative de l'avancée scientifique - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Credit

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Allégorie de la science - Fresque du Forum du Palais de la Porte Dorée, Pierre Henri Étienne Ducos de la Haille

Photo : Lorenzö © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022