Janniot’s bas-relief

Featuring a series of allegories, in the midst of abundant fauna and lush flora, this “stone tapestry” measuring 1,130 m2 exalts colonial wealth. It was produced in under 2 years by Alfred Auguste Janniot, a sculptor specialised in monumental decors, and was intended as an illustration of the economic contributions made by the colonies to metropolitan France.

Legende

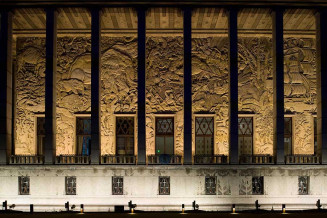

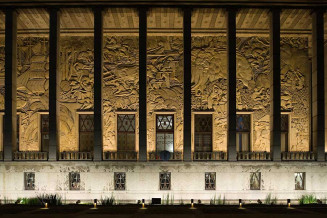

Façade du Palais de la Porte Dorée

Credit

Photo : Pascal Lemaitre ©Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2018

A technical feat

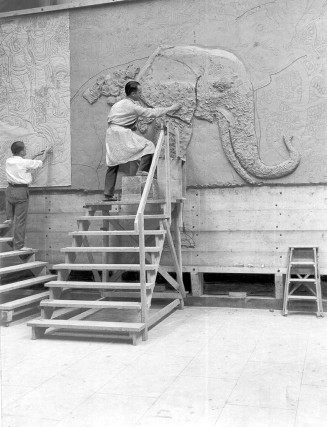

Between 1929 and 1931, for the Palais des Colonies, Alfred Janniot – assisted by his collaborators Gabriel Forestier and Charles Barberis and 30 specialist workers – achieved a true technical feat in scarcely two years, by sculpting this bas-relief with a surface area of 1,130 m², a height of 13 metres and a length of 90 metres. Described as the world’s biggest bas-relief, it covers the entire façade of the Palais de la Porte Dorée.

Legende

Praticiens en train de reporter un dessin sur le modelage en terre

Credit

© Revue L’Illustration n°4532, 11 janvier 1930

To create this monumental work, Alfred Janniot called on the classic techniques of sculpture. Starting from sketches, he and his collaborators first modelled fragments of the bas-relief in half-size from clay in his workshop, based on live models. The clay reliefs were then cast in plaster. Lastly, these plaster castings enabled blocks of Poitou stone 10 cm thick to be cut straight from the façade of the Palais.

The bas-relief adopts its author’s codes of classic culture: there is no perspective, all the silhouettes, placed on a vertical plane, are on the same scale, and the architect of the Palais, Albert Laprade, thus referred to a “stone tapestry”. Note that, as in ancient tapestries, the characters’ feet are not visible, except for the ones at the bottom, to avoid giving an impression that they are floating. The entire composition was sculpted so as to leave no empty space. The sculpted characters are all larger than life so as to be easily visible from the forecourt at the foot of the Palais.

Legende

Les sculpteurs Alfred Janniot et Gabriel Forestier devant un modelage en terre

Credit

© Thérèse Bonney 1931 BHVP

A classic and allegorical inspiration

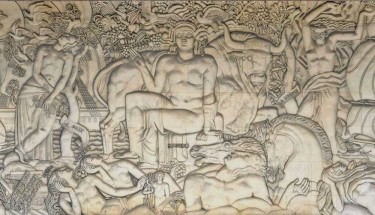

Just as Christ was majestically sculpted in the centre of the tympanum of Roman and Gothic cathedrals in the past, the central figure in the bas-relief symbolises Abundance, adopting an aloof posture, making it a deity. It is leaning against a powerful ox, symbol of strength and wealth, and framed by two trees loaded with symbols: on the left, an olive tree representing peace and, on the right, an oak tree representing freedom, with each of these two words written in a speech bubble.

Legende

La figure centrale de l'abondance du bas-relief

Credit

© Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

The figure of Abundance overlooks the ancient deities: Apollo with his horses and the two mythological allegories representing fertility and abundance: the goddess of the harvest, Ceres, adorned with ears of wheat, and the goddess Pomona, adorned with fruits.

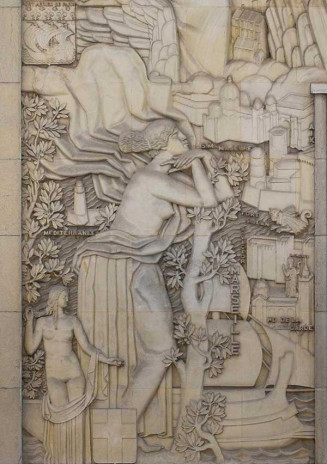

The area around the large entrance door features allegories of the big French ports where merchandise is arriving from the colonies, identified by their coats of arms: Marseille, with its symbolic monuments and the Mediterranean; Bordeaux with its caravels and the Garonne; Le Havre, with its ocean liners and cranes. Lastly, Paris is symbolised by its “air port”, in other words Le Bourget airport, represented by an airplane.

Legende

Détail du bas-relief : le port de Bordeaux

Credit

© Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Détail du bas-relief : le port de Marseille

© Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

The treatment of the nude, the central figure in western sculpture, from the beautiful ideal of classic Antiquity to the medieval Christ suffering on the Cross, reveals the influence of Janniot’s classic culture: the bodies are draped in ancient style, especially the dozen European figures, male and female, half-naked in the central part, revealing “conventional” muscular perfection.

Realistic representations with ethnographic accuracy

Scène de chasse à l'hippopotame du bas-relief

Photo : Pascal Lemaître © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

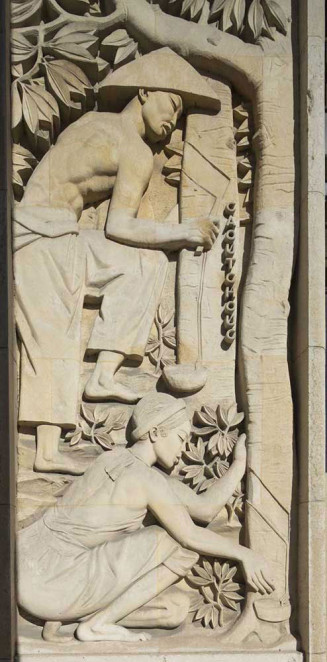

Alongside these classic references however, the illustrations of 157 human figures on the bas-relief were produced in a realistic style.

The bodies are magnified and sculpted in all their materiality: veins show under the skin of the forearms, the muscles are prominent under the skin of the back, and the facial features are identifiable, like the scarred faces of the hippopotamus hunters.

Since the light, monochrome stone of the bas-relief does not allow the different skin shades of the characters to be differentiated, their identification comes from the precise depiction of their features and ornaments, from their hair styles to their clothing. Nudity is used at the service of realism, inspired by the autochromes in Albert Kahn’s collection “the Archives of the Planet”, created between 1909 and 1931. Whereas, on the bas-relief, the women of Asia and North Africa are all wearing clothes, their heads are also covered, and the men of Asia are bare-chested only within an aquatic context (fishing or rice fields), the men and women of Black Africa are depicted bare-chested, dressed in a simple loincloth.

Legende

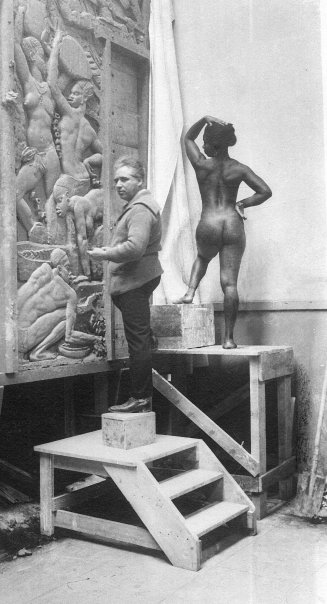

Janniot dans son atelier en train de modeler d'après un modèle vivant

Credit

© L'Illustration

Janniot sculpted from live models, as can be seen from the many photos taken in his workshop. From 1929 on, he documented his work closely, collecting photographs and statistics about the wealth of the colonies, going to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and the menagerie at the Jardin des Plantes to make sketches of plants and animals.

His intention was to illustrate exotic flora and fauna in a faithful and naturalistic – documentary even – manner, like the many Art Deco bronzes of animal figures in fashion since the 1920s. His bas-relief is a veritable bestiary, illustrating with almost scientific accuracy over 215 animals of all species: insects, fish, molluscs, birds, reptiles, wild and domestic mammals…

Likewise, costumes, hair styles, the technical gestures of craftsmen and farmers are represented with ethnographic precision. Even though Janniot had never travelled to the colonies, these were not imaginary illustrations, a source of disembodied or caricatured stereotypes – a criticism made of the orientalist painters of the 19th century. On the contrary, this was a realistic representation of individualities, which was something new for that era.

Exotic imagery

The colonies are distributed on either side of the bas-relief based on a geographic and symmetrical rationale. In the West – in the left-hand part – Africa, Indian Ocean and the West Indies. In the East, Asia and the Pacific islands. They are depicted via their geographic name, their indigenous populations and the wealth from their farmland and mines exported to France.

Legende

Le bas-relief du Palais côté Afrique

Credit

Photo : Cyril Sancereau © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

Le bas-relief du Palais côté Asie

Photo : Cyril Sancereau © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

This was not a simple utilitarian vision of the colonies: hippopotamus hunts, African canoers, North African weavers, the vernacular arts represented by Asian statuettes, harvesting food, all these things illustrate local and traditional know-hows, far-removed from the farming methods of the colonists (intensive crop-growing, mechanised production and transport…). Wild animals are abundantly present on the bas-relief (elephants, lions, antelopes, tiger fighting a python, monkeys…) and are not subjected to colonial exploitation.

Legende

Représentation d'antilopes sur le bas-relief

Credit

Photo : Pascal Lemaître © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022

The figure of the colonist is absent from this ideal portrayal. The exotic imagery, presenting an enthralling vision of a peaceful world seen as a land of celebration, is free of violence: there is no reference to forced labour and abuse. This is an illustration of the theme of abundant lands, where man lives in harmony with a lush and generous nature, directly in line with the paintings of Douanier Rousseau, who died in 1910.

But this fantasized golden age is not just the fruit of an “Eden-like” relationship with nature, since the sculptor depicted – like a frieze crowning his composition – a large number of cities that are architectural masterpieces testifying to prestigious civilisations: temples of Angkor on the right, Arab cities with their minarets and fortified walls on the left.

In this institutionally commissioned work, tasked with glorifying the French imperialist plan, Janniot’s aim was to mix nature and culture to increase the public’s fascination with an exotic and idyllic “elsewhere”.

Legende

Détail du bas-relief, Cambodge

Credit

Photo : Pascal Lemaître © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

Détail du bas-relief : récolte du café, Sénégal

Photo : Pascal Lemaître © Palais de la Porte Dorée © ADAGP, Paris, 2022