The Tropical Aquarium or colonial waters section

As a counterpart to the zoo at the 1931 Colonial Exposition, predecessor of the future Vincennes Zoo, the review commission for the permanent Musée des Colonies validated the construction of a definitive Aquarium within the Palais de la Porte Dorée on October 9 1929. The objective was to put the exploitable marine and river fauna of the colonies on public display and, immediately after those, the many products and sub-products of their exploitation, to gradually compensate for the thinning out of fish stock in metropolitan France.

Attraction of the 1931 Colonial Exposition

The creation of this “colonial Aquarium” represented a new and hitherto unknown attraction in France: the spectacle of colonial fish placed, wherever possible, in their biological environment. The completion of this project also meant that Paris was now endowed with an institution that the big world capitals already possessed.

The Aquarium project and the Exhibition of marine and freshwater fauna and their industrial exploitation was entrusted to Abel Jean Gruvel, (1870-1941), director of the Colonial Fishing Laboratories at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, who had been doing research and consultancy work since 1912.

Vue du terrarium en 1931

© Musée du Quai Branly

The Aquarium, set up in the basement of the Musée des Colonies, presented to the public a series of 56 tanks grouped together in 3 sections. The freshwater and seawater sections were organised around the large square room and the third, the acclimated exotic fish section, made up of small and medium-sized tanks, was positioned under the staircase of honour. Between the tropical aquarium and the large aquarium there was a terrarium pit, containing the crocodiles and turtles. In the centre of the large room, an elliptical pit housed an animated, illuminated planisphere showing the formation of the French colonial empire.

In the marine aquariums, which included two large tanks 3.50 metres long, an unprecedented size anywhere in the world, the public would discover fish, crustaceans, turtles, sharks, such as dogfish and hammerhead sharks, large stingrays, along with sea anemones and a variety of molluscs, squid, cuttlefish and octopuses. The second section would present species originating in Indochina, Equatorial Africa, India and Guyana, such as goldfish, silurid fish, angelfish and piranhas. The third section displayed a number of exotic species that had acclimated in Europe, such as the American perch, tench, ide or the yellow-gold “canary” wrasse.

Photo extraite du film d’Albert Mourlan présenté lors de l’exposition coloniale, catalogue de l’exposition « L’application décorative du poisson exotique »

The capacity of the large tanks allowed for the shooting of a film showing turtle fishing, Madagascan style. Unfortunately this unique film was destroyed during a fire at one of the Albert Mourlan studios.

Legende

Vue de bacs présentés en 1931

Credit

© Musée du Quai Branly

Vue de bacs présentés en 1931

© Musée du quai Branly

The terrarium, a freshwater tank surrounded by vegetation, housed many specimens of reptiles and exotic batrachians: crocodiles, alligators, lizards, frogs and toads. For Professor Gruvel, the aquarium should allow for a scientific but also artistic presentation. “We would like the public entering the Aquarium to really feel that they’re in a vast grotto surrounded on all sides by water and able to glimpse at its inhabitants through openings in the wall, like big glass portholes in an enormous submarine.”

He entrusted Roger Landois, a painter and sculptor, with the decoration of all the tanks in the Aquarium. To reconstruct the aquatic environments, he designed each aquarium like a painting. To highlight the different varieties of fish, avoid obstructing their movement in any way, and give the illusion that they were not confined, he created a wide variety of arrangements for the tank bottoms, stones and plants extended by paintings on glass placed in the bottom of the tanks. “Here, a greenish colour really brings out the red in the fantail fish. There, in the reconstituted seawater, actinia flourish for the enjoyment of the Sumatra fish who love to whip up little clouds of sand. Finely-laced gorgonian coral that the seahorses cling to, dark, defined slate décor like the outline of the silurid fish, marble décor, crevices, grottoes, stacks of granite climbed repeatedly by the green sea turtles” writes Mr. Landois. Everything could be disassembled and, should an epidemic occur, the tank bottoms could be removed, the stones pulled out, and disinfection would be complete.

Legende

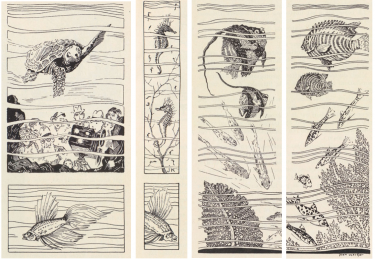

Illustrations de l’aquarium de Jean Kerhor dans le magazine TOGO-CAMEROUN, avril 1932

The exhibition of products from colonial waters displayed all the products and sub-products that marine animals could provide as a result of their exploitation.

For the fish, two large display cases showed the naturalised species with the greatest value from an edible or industrial viewpoint, then the boats and tools used to capture them. A large display case featured dried, salted fish, canned goods, oil, flours and glues. Another display case showed the use of shark and stingray skins in the form of bags, shoes, shagreen leather, etc.

To complete the exhibition, other display cabinets featured the main marine colonial products: tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, pearls, corals and sponges, alongside naturalised animals.

The transformations of 1934

When the Colonial Exposition ended, the Aquarium did not close and continued to be developed through the installation of a large terrarium in 1934 to house the illuminated planisphere. For its design, Roger Landois came up with the idea of reproducing a piece of Equatorial Africa: “A rock, 5 metres high by 7 metres long, waterfall 2.80 metres, with water flow of 600 litres a minute at 25°, three 15 m2 tanks and a sandy beach, also 15 m2. Then in the centre of the room, the biggest of these "landscapes", the crocodile lair, 3 to 4 metres.”

No less than 45 tons of stones were required to build the barricades for the large terrarium, a new ultraviolet and infrared lighting system to replace daylight and special ventilation to welcome the crocodiles.

In 1934, the Aquarium inaugurated its first temporary exhibition: “Decorative application of the exotic fish”, which featured almost two hundred artefacts. The catalogue published for the occasion is kept in the Museum’s archives and describes the diversity of loans secured from private owners and the Sèvres Porcelain Factory. Hence, displayed alongside a watercolour by Odilon Redon were stoneware models by E.-M. Sandoz, wooden carp and decorative panels by G.H. Laurent, and stained-glass boxes by Auguste Matisse.

During World War 2, the Aquarium was placed under the authority of the Germany army, which received proposals for changing the heating system for the terrarium to reduce costs. The SS gave Aquarium staff authorisation to fish in the Seine as a means to feed the Aquarium’s tropical species.

Although the objectives of the Tropical Aquarium these days are diametrically opposed to those of the Colonial Exposition, since the goal now is to contribute to the conservation of natural environments and protect endangered species, the very ones whose exploitation the original designers were encouraging in 1931, the arrangements of the tanks and terrariums remain identical to what a visitor to the Colonial Exposition would have seen.