The architectural instructions for the Palais de la Porte Dorée

Legende

Construction of the permanent museum of the colonies

Credit

© Thérèse Bonney 1931 BHVP

Design of a propaganda building

On March 17 1920, a law was passed approving the organisation of an interallied exposition in Paris in 1925 with the creation of a permanent museum of the colonies. Gabriel Angoulvant, governor general of the colonies, was named general commissioner of the exposition, the main goal of which was to legitimise colonisation in the eyes of the French, who were sceptical about colonial action, which they knew little about and viewed as costly and pointless.

No specification was given as to the exact nature and content of the museum, which was to have an immediate educational purpose, read like a page from the “great book of the Colonies” and symbolise the vast colonial empire, to quote Marcel Olivier, author of the general report on the international colonial exposition.

In 1926, Léon Jaussely was appointed Chief Architect of the Exposition and tasked with the construction of the Museum. It took seven years to obtain approval for the principle of a colonial exposition in Paris; it would take another eleven years for the International Colonial Exposition to see the light of day.

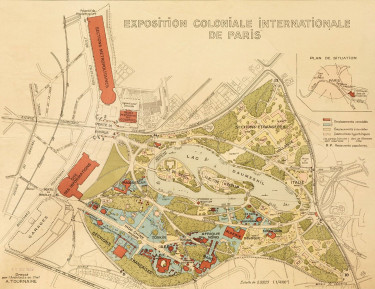

One of the first problems to come up in producing the exposition was its location. After moving from the Bois de Boulogne to the Champ de Mars and then to Vincennes, the Bois de Vincennes was definitively chosen in 1926. Through that decision, the organisers wished to be seen as initiating new urban planning in the east of Paris thanks to the completion of the no. 8 metro line.

Legende

Plan de l’Exposition coloniale internationale par Albert Tournaire, 15 décembre 1928

Credit

© AN

The initial projects

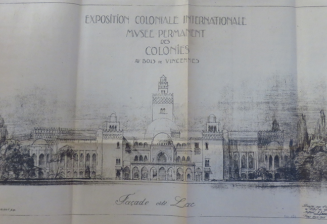

Premier projet du musée permanent des colonies en décembre 1926 situé en bordure du lac Daumesnil

© ANOM

Léon Jaussely presented an initial project in December 1926 located on the edge of Lake Daumesnil, in the place where the Madagascar Pavilion would later be situated. The project took into account the fact that the Palais would be used during the Exposition by the Algerian, Tunisian and Moroccan commissions, whose governments would contribute to the costs of construction. So it was developed in a mixed “North African” style and comprised a large central minaret in the style of Koutoubia (minaret of the Marrakech mosque dating from the 18th century) and white cupolas.

To prevent this construction at the entrance to the wood from creating a screen that would have hidden the view of the foliage and Lake Daumesnil, the technical committee of the International Colonial Exposition (ICE) validated the change of location of the future museum, moved from Lake Daumesnil to the Porte Dorée, lining up with the monumental entrance to the Exposition on Avenue Daumesnil.

On March 10 1927, the technical committee decided that Jaussely was not capable of directing the construction of the museum, considering him to be “a travelling city planning salesman, and a great artist who has never produced anything” (Letter dated February 25 1927 from Albert Laprade to Henri Prost), and came together to appoint Jaussely’s second-in-command. There were two candidates: Robert Fournez and Albert Laprade. Jaussely was opposed to Fournez and so Laprade was named as his second-in-command, and in reality his associate. Moreover, the post of Chief Architect for the Exposition was taken from Jaussely and entrusted to Albert Tournaire.

Based on a succinct programme dated April 12 1927 written by Général Angoulvant, Jaussely worked on a new project, which was presented to the technical committee in the presence of Laprade on May 27 1927 in a clearly “Khmer-Indochinese” style for both interiors and exteriors.

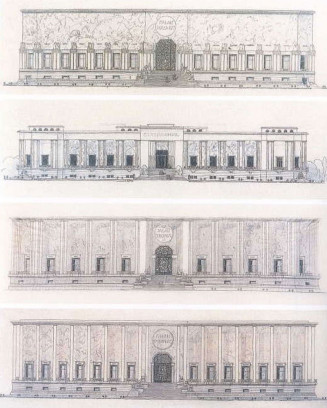

Legende

Projet de façade présenté au comité technique du 27 mai 1927

Credit

CAMT 1997 025 471

The project was not well received by the committee members who found no reason to adopt an “Indochinese” style rather than a “North African” or “Sudanese” style and even less of a reason to mix them.

Albert Laprade presented a series of perspective sketches of the main façade. The committee members selected the one depicting the idea of a large stone tapestry in warm tones, featuring coloured and gold highlights, with the tapestry sheltered by a sort of light canopy, “evoking the countries of the sun in a neutral, modern style, presenting a façade with square pillars and a long stone tapestry” (Letter from Laprade to Lyautey, 1927).

Legende

Albert Laprade, série de croquis en perspective

Credit

© AN

Croquis en perspective de la façade du Palais de la Porte Dorée, réalisés par Albert Laprade.

© AN

The architectural style

Laprade provided an answer to the question of the architectural style to be adopted for the Musée des Colonies. Should the Palais be built around “modern taste” (monochrome architecture affirming the structural design and featuring décors based on stylised motifs), or should they opt for neo-classicism (architecture using Greco-Roman elements highly valued for public buildings in the 19th and early 20th centuries), or for an Art Deco style (taking its name from the exposition internationale des arts décoratifs of 1925, and whose architecture is characterised by very geometric outlines with a heavy focus on decors and materials), or an exotic or neo-colonial style (architecture combining different architectural styles developed in the colonies)?

As Laprade saw things, his project should be modern and simple, with a slightly novel style, neither cubist, nor pompous. Modernity was expressed through the height and nervous slenderness of the colonnade, simplicity by the rectangular shape, with no angled corners and no acroterions or pediments. And to allow the project to bring simple forms to life, Laprade played on the material and colours of the stones used in the veneer.

« The general principle behind the façade is a large, very colourful and brilliant tapestry, engraved into polished stone in warm tones, the background enhanced with gold and protected by a canopy in a cold colour, base and moulding in grey granite, and columns set with polished white granite.»

Albert Laprade

Laprade insisted on the relationships between colours, the balance of values created by the juxtaposition of materials in different tones. Alongside a warm-coloured stone, he would choose another one that was colder; in so doing, he developed a system of values which, chosen for their contrast, answered each other and formed a whole.

A new project was “hastily” put together by Laprade and was examined on July 27 by the aesthetics committee of the City of Paris. The day before the meeting, the architect was afraid his project would not be accepted.

« I fear that this learned commission made up of venerable members of the Institute, high-level civil servants with a plethora of degrees, won’t understand the idea at all, will be critical on principle and demolish the whole thing with a few apparently unimportant requests. »

Certain city counsellors expressed great hostility to the project. The committee required the height of the building to be lowered, the portico widened by 3 metres and they wanted round or octagonal columns, 13 metres high maximum, crowned by a larger entablature.

Moreover, in July 1927, Maréchal Lyautey, Resident-General of the French protectorate in Morocco since 1912, was appointed high commissioner of the future Colonial Exposition. Lyautey had returned from Morocco in October 1925, in complete disgrace after Maréchal Pétain had stripped him of his military power. His desire to promote true Moroccan cultural development and local administrative autonomy had made him intolerable for the French government, which was opposed to any decentralisation and supportive of the rapid and forced assimilation of colonised countries.

As soon as he took office, Maréchal Lyautey postponed the Colonial Exposition to 1931 and opposed the Musée des Colonies project in Vincennes. He would hear no talk of a museum (“a cemetery”), nor of Vincennes as its permanent location. His sole objective was the creation of a “Palais des colonies”, a sort of “information centre” in the very heart of Paris.

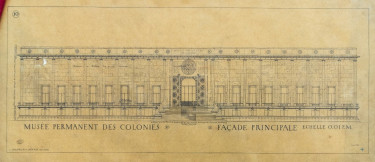

On August 5 1927, Laprade presented a new project to the aesthetics committee with octagonal columns and an attic. The project measured 20.40 metres high including a foundation 4 metres high; the portico was 3 metres deep; the reduced columns were still octagonal and crowned with an acroterion. He defended the “slenderness” of the columns. For him, the weight-bearing elements were not in the Neo-Greco tradition but the expression of a new aesthetic.

« The Egyptians made heavy columns, the Greeks made them increasingly light: Doric, Ionic, Corinthian; the Gothic designers were outrageously bold. It would seem strange now that we have reinforced concrete not to be able to use all the audacity that this material allows. ».

Laprade also noted that they were already twice as big as required for the load they were bearing.

Nevertheless, the project for a purely classical collage, just what Tournaire had wanted, was the subject of the first invitation to tender for work on the permanent museum.

Legende

5 août 1927, façade principale du Palais de la Porte Dorée, par Albert Laprade

Credit

© AN

The state of public finances after the war forced expenses on the project to be cut. On October 7 1927, the architects presented the following proposals: more economical materials for the façades, use of rubble stone sourced from the demolition of fortifications, reduction of building size. For Laprade, reducing the dimensions of the project also meant the opportunity to re-submit his initial project, notably in terms of the shape of the columns and removal of the acroterion.

In a letter dated November 9 1927, addressed to Blanchet, president of the technical committee, for one last time Laprade defended his project, described as too simple and too modern. He responded to the simplicity argument with the beauty of the materials and the large stone tapestry that wasn’t effectively rendered by the drawings. To the various questions about the style, expressed through the shape of the columns and the width of the peristyle, he proposed slender, square columns, with no acroterion to assert the modernity of his project and through a “spirit of conciliation”.

The initial façade of the museum was finally validated by the technical committee and approved by the High Commission of the Exposition. But Laprade now had to convince Maréchal Lyautey, with whom he had had no contact since 1922 and who moreover believed Le Corbusier to be the ideal architect. On January 12 1928, Laprade presented a plea in favour of his project, which he described as simple, noble and “anti-cardboard” in a total reaction against the “Exposition” style. He briefly mentioned the bas-relief, his main idea, as the only thing capable of evoking all aspects of colonial life.

On January 19, he finally met with Maréchal Lyautey who laid down the following directives:

«I’m only interested in one thing, Paris. Practical buildings with no frills, business buildings, very American-looking. Vincennes, I just can’t see that. I don’t think the location has any value. I don’t know what this building is a response to. In fact it could even serve as an annexe to Paris. Absolutely not luxurious. Le Corbusier, amazing.»

The Maréchal was not convinced by Laprade. But urged by the government, which felt that the museum project was too far along to change their minds, he reluctantly accepted the construction of the permanent museum in Vincennes. On January 20 1928, the permanent commission for the exposition, presided over by Maréchal Lyautey, validated the principle of the Palais in Vincennes, with the exception of the decoration.

On July 31 1928, a private contract was signed with the building contractor Lajoinie, and the building work could now start. All that remained was to get the Maréchal, a fervent admirer of avant-garde nudism, to accept the stone tapestry, whereas Laprade had already made contact with the sculptor Alfred Janniot, who he believed was the only one able to head up a project of this scope.

On September 5 1928, Laprade explained the situation to Janniot:

«The Maréchal wanted to have an information office within Paris, he didn’t like the principle of the building being in Vincennes, and he thought that we needed a building made from simple, reinforced, whitewashed cement. To avoid a clash with him, the entire general staff of the Exposition agreed on a conspiracy of silence with regard to the “decoration” issue, until the start of work on this building whose very principle was under dispute. The invitation to tender was finally launched a month ago. The first stone must be laid in 2 weeks. Now that the building work is underway and that the Maréchal is starting to get used to its appearance, we can begin talking about the decoration.»

The debate began and certain members of the various commissions claimed that it was risky to entrust the work to a single artist, and that they should seize this remarkable opportunity to bring all the masters of French sculpture together to partner in the production of a collaborative work. On December 4 1928, the Maréchal opted for Laprade’s approach, deciding that only the master-architect should present a name. To his credit, Maréchal Lyautey, who was behind neither the project nor Laprade’s choice, gave the architect the means to make his total work of art happen. He also gave him complete freedom in terms of sculptors, painters, ironworkers, furniture designers and decorators, thus expressing his full confidence and the extent to which he recognised Laprade’s talent. His only demands concerned respecting deadlines and the allocated budget.

Through this project, Laprade demonstrated his perfect mastery of forms and composition, which Janniot’s work revealed with talent, while responding to the wishes of the Exposition organisers. The façade informs visitors of the monument’s purpose and encourages them to enter thanks to the perfect integration of the bas-relief into the structure of the edifice.

On November 5 1928, the first stone of the Musée des Colonies was laid; building work was finished on May 6 1931, with the inauguration of the International Colonial Exposition.